In honor of the Film Preservation Blogathon, Oregon Movies, A to Z asked Dennis Nyback to talk about nitrate film. Nyback was a union projectionist in Seattle before opening his own movie theater in 1979, which started him on an international career as a collector and curator.

1. When/where/how did you learn to project nitrate film?

I was never taught to project nitrate film. I was taught to project 35mm film. I had one lesson on “threading” the projector and making a change over. After that I learned on the job. After about six months I really knew what I was doing.

At that time if I had been handed a reel of nitrate film I would have had no idea what it was. Cursory inspection of a reel of nitrate and a reel of safety film would not reveal any difference. The weight and dimensions are the same. Both would be projected in exactly the same way. Only later did I find that looking at the edge codes for the words”safety” or “nitrate” would reveal the difference. Tearing off a piece at the end and lighting it with a match is another way to check. Safety film will slowly melt. Nitrate will burst into flames.

I did learn about nitrate, but in a more casual way.

After I got into the Seattle projectionist union in 1977, I worked in many theaters that had been built during the nitrate days. Those projection booths had metal lined walls and ceilings, guillotine type shutters for the projection port windows, and “heat fuse linked” metal chains hanging over the projectors. The chains were connected through rollers to heavy weights and then to the shutters. The chain was also connected to the projection booth door. In the event of a nitrate fire the heat would melt the the “fuse” and the weights would drop, the port windows would all slam down and the door would slam shut. It was a neat system, since a fire in either projector would have the same result. The idea was that the metal walls and ceiling would contain the fire, and only the projectionist would die if he didn’t get to the door fast enough.

In just about every booth I worked in I found this archaic system still in place. It wasn’t in the way, so there was no reason to do remove it.

Two projectors were used because film came on twenty minute, two thousand foot, reels. Every twenty minutes the projectionist would change from one projector to the other. The crowd had no idea what was going on. With the advent of Xenon projection lamps which replaced the carbon arc system, automation became the norm. Automation used a single projector. The film would be spliced together to run continuously from opening title through the credits. I became curious about the heat fuses and shutters and stuff and was told by older operators about nitrate film. Like everyone else, I assumed that nitrate had been discontinued over safety concerns.

It was my buying a very old 16mm film in the early eighties that led to the correction of my error. It was an original World War I newsreel.

I asked the projectionist Doug Stewart if this 16mm print could be nitrate. He told me there had never been any 16mm nitrate. I asked him, if they had safety film that long ago – in World War I – why did they keep using nitrate into the fifties?

Doug said “Because it looked better.”

Nitrate film had a very high silver content. If you see it on the screen you’ll be struck at how black the black is. If you pause to think, you’ll realize that you’d never really seen black in a motion picture before. Safety film is literally a pale imitation of the gold standard of nitrate.

Television cut into the profits of the studios in the fifties. Before that there was never a need to cut corners by getting rid of nitrate. At the same time the Hollywood studios were searching for ways to keep the profits up, introducing Cinemascope, 3-D, and stereo sound, they were dumping nitrate for the cheaper safety film. If you think about, if nitrate was so dangerous, why did we end up tearing down most of the old movie palaces, when they should have burned down by themselves long before that.

2. Did you ever have any close calls, safety wise?

I would generally stand by with a fire extinguisher in my hand just in case whenever I would project a nitrate print ( Ed. note: he means from his own collection). No, I never had a problem. Nitrate film first used during the first twenty years of the century was much more flammable than later nitrate. The early years were when most of the nitrate fires happened. The really big fires occurred in film storage buildings. That is one reason so many films from that era are now lost. The newer nitrate was generally referred to as “safety nitrate.”

There were other safety measures to prevent nitrate fires. The projectors had ‘fire rollers.” Those were rollers at the top and the bottom of the projectors that were calibrated to snuff out any burning film that passed through them. In most instances they worked well and the take-up (bottom) reel almost never caught fire. The greater risk was the fire would jump to the top reel. A fire would almost always start with the film jamming in the film gate with the heat of the projection light igniting it.

In most instances there would be flash of flame and then it would go out. If it jumped to the top reel the fire shutters would slam shut. A projector also had a “fire shutter.” That was device that blocked the projection light from going through the gate. As the projector gained speed it would rise up. If the projector stopped it would drop down.

Most of the heat in a projector came from the light. The shape of the projected picture is cut down from round to square by the “aperture” plate, which is in the projection gate. It would get very hot. Projectors in the bigger theaters were “water cooled”. Water would run from a pipe in the wall through steel or copper lines to cool the gate. The film reels were also contained in a metal housing with a door that swung open to enter or replace a reel. In most modern theaters the doors were often removed just to make the job a little easier.

The Stanford Theater in Palo Alto has been running nitrate prints for the last thirty years. Last year it had a fire. Apparently all the safety measures worked and the fire was contained in the projection booth. Most of the damage was caused by the water sprinkler system.

3. Did you ever hear of other projectionists who had close calls?

On my website, you can read a story I wrote about a nitrate incident that happened in Seattle in the thirties. The story was told to me by the projectionist Ash Bridgeham. I trained with Ash at the Duwamish Drive-In Theater at the same time I was working at the Green Parrot Theater. Ash had entered the projectionist union in 1927.

There was another funny nitrate story from the Embassy Theater. I worked there in the early eighties. There was a big dent in the metal ceiling above the toilet in the corner of the projection booth. The story was that a reel of nitrate had caught fire and the projectionist had grabbed it and tossed into the toilet and the toilet had exploded. A new toilet was installed. A while later the projectionist was cleaning his gun, or something like that, when it went off. The bullet struck the toilet and broke it a second time. The dent was either from a piece of the first toilet, or the second, hitting the ceiling.

I worked with dozens of old guys who had run nitrate. Those are only actual fire stories I ever heard.

The stuff didn’t just burst into flames by itself. You should realize, movie theaters weren’t the only places where nitrate film showed up. It was the film stock shot and processed all over the world. It was routinely shipped on trains, boats and planes. I have some of the old containers used to ship nitrate prints. The only difference between them, and newer containers, is the presence of stickers saying to keep the container away from open flame. The tank of gas in your car is a lot more dangerous than a nitrate film print.

4. You said you preferred jobs projecting nitrate. Why?

I never said I preferred jobs projecting nitrate. There were no jobs projecting nitrate. It wasn’t just from another era, it was against the law. What I did prefer was to show movies with carbon arc light. When Ash Bridgham retired in 1980, the Duwamish Drive-in closing down, the projectionist union president, Tommy Waters Jr., wrote “All the different forms of automation are upon us here in Seattle. We have only five theaters left that are manually operated with carton arcs.” I think I worked at all of them. I ran carbon arc reel to reel at the Moore Egyptian, Embassy, Duwamish, Bellvue, Northgate, Southgate and King, theaters, and maybe some others. To me it was the standard, as opposed to exotic.

I first used carbon arc at the Moore in 1975. The last place I ran carbon arcs was at the King Theater in the early nineties. That was a 70mm house. Many smaller or medium size theaters used copper clad carbons that were 8 and 9mm. Those were about as big around as a pencil. Big theaters used 13s and 14s. Those rods would be as big around as your thumb. One of my great pleasures was running Lawence of Arabia in 70mm with those huge carbon arcs putting the beautiful light on the screen.

5. Can you explain the mechanics of carbon arc projectors? Is it true that the image on the screen comes from a complex interplay of fire and water, light and dark, dream and material reality — all interacting in real time within the projection booth, under the supervision of a real live human being? Tell us how it works.

You got that right! Film is a very tangible thing. You can hold it in your hands. You can look at it against a light and see the picture. It is for all intents a series of photographs, or more properly, photographic slides. It is a directly captured moment in time. Digital looks at an image and breaks it into little pieces and then puts it back together again. It is the difference between a Vermeer and a jigsaw puzzle.

I already mentioned the water cooled gate. The fire is from the carbon arc light. To put the picture on the screen you have to set it in motion at 90 feet per minute. It is carried through the projector by spinning teethed sprockets meshing with sprocket holes on the edges of the film. If you projected a beam through the film outside the gate you would have a blur. The film has to stop briefly while it is running. Below the gate is what is called the intermittant sprocket. There are four sprocket holes per individual frame of film. The intermittant pulls the film down four sprocket holes and pauses and does that 24 times per second. .At the same time a shutter is cutting off the carbon arc light 24 times per second to coincide with the pull down movement of the intermittant. The light only passes through the film when it is stopped. There is a brief flash of dark every time the shutter cuts the light. Something called “persistence of vision” keeps you from noticing that.

Carbon arc lamps have a small open flame that burns very very bright. Old search lights used carbon arcs. If you see old movies of search lights scanning the sky you are seeing how a carbon arc light could put a light on an airplane in the sky. Spotlights in theaters, such as the Super Troupers, used carbon arc.

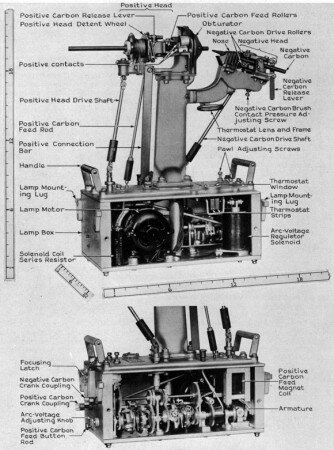

The way it works is that inside the lamp house two rods, held by metal teeth, would face each other across a short gap. The rods are placed there by the projectionist with the lamp house door open. That was called “trimming” the lamp. The door is then closed. Each rod is connected to direct current electricity from a rectifier. A switch turns on the current. The projectionist gives a knob, about the size of a door knob, a quick turn, which kisses the two rods together, a flame is created, and then with the a quick reverse of the wrist movement, pulls the rods apart just enough to keep the flame arcing between them. A concave mirror in the back of the lamp house turns the arc light to a reflected beam. The beam goes through a condenser lens, the motion picture film, the projection lens, and puts the the picture on the screen.

The rods consume themselves as they burn. A small motor in the lamp house moves them inexorably together as they use themselves up. You can monitor the arc through a dark view window and adjust it, if it varies from perfect. If you were to look at the open flame you’d be blind in nothing flat. The lamp houses have little metal chimneys on the top of them for the smoke to go out . Underneath the arc is usually a small removable square pan. The copper casing on the rods fall off in drips. The drippings fall into the pan. In most booths there would be a coffee can at the base of the lamp to toss the copper drippings into. The copper in the cans would then be collected at the union hall and sold as scrap. The proceeds went to the Jimmy Fund. Most booths had a sign spelling out the practice. In the days when every theater in America used carbon arcs, the era extending into the early seventies, the drippings generated real money for the charity.

Carbon arc was replaced by Xenon starting in the fifies. A xenon lamp is more or less a very bright light bulb. The carbon arc rods were petroleum based. When the first oil embargo happened in 1974 the price of carbons doubled and it was downhill from there. A xenon lamp also doesn’t need to be trimmed. It just turns on and off and gets replaced every three thousand or so hours.

There is an aesthetic difference in the lights. Carbon arc is warmer and more representative across the color spectrum. Xenon often has a cold, blue tinge to it, some more so than others. You might not notice it in a multiplex. At the Film Forum in New York City they do reel changes with xenon lamps. The color difference between the two projectors is jarring, especially with black and white film. Xenon lamps were the first nail in the coffin for the projectionists. Automation followed and the projectionist unions shriveled up and died. In the early days of movies the films were hand cranked. There was also no motor advancement for the carbon arcs. It generally took two operators, one to crank the projector, and one to feed the carbon. The reels then were only 1000 feet, or ten minutes each. It must have been a choreographed art to have the carbon feeder, at the end of a reel, move to the second projector, strike the lamp, and crank the next reel up to speed for the change over.

6. As a private collector yourself, are there any nitrate films you want to see preserved, or lament because they were not preserved?

Any nitrate film should be preserved as long as it is in good condition and runnable. It is possible to open a can that once held a reel of nitrate and find only dust inside.As the film deteriorates the more flammable it becomes. There is a lot of old nitrate out there that is all that remains of specific films. A tremendous number of silent films are unaccounted for. The Vitaphone Project has done a great job in getting nitrate originals married with their sound discs and then printed as safety film. They have a backlog of projects that are waiting funding. There are tons of nitrate prints in a bunker in Denmark. Hard to say how much is squirreled away in various other places around the world. All of my nitrate prints are now in LA in a special warehouse for nitrate.

I’d like to see nitrate routinely screened. The Hollywood directors in the silent era and into the fifties were masters of lighting. All of their calculations were predicated on nitrate film being the conduit of their vision. You might be knocked down by the visual beauty by a Hitchcock, Ford, Hawks, Borzage, Murnau, or other old Hollywood film you see now, but you aren’t seeing the film as the director intended it, or as the audiences first saw it when it came out.

Do I lament things not preserved? Here is a specific story. In the late nineties I was at the 6th avenue and 26th Street flea market in New York on a brutally hot summer day. On an open table, baking under the sunlight, were dozens of old film cans. I opened one can up and found a good condition silent nitrate reel. I opened another can and found a good sound reel. I went to the guy in charge of the table and offered him a hundred bucks for everything on the table. He refused the offer. That meant I had to look into more of the cans. I found that maybe half of the cans contained dust, or deterioration. I walked back to the guy and told him my offer was now fifty bucks for everything on the table. I also told him it was nitrate film and shouldn’t be out in the sunlight. He told me that if no one bought the film that day they would take it back to their store and I should check in on Wednesday, the next day they’d be open.

On Wednesday I went there. I was told that they had freaked out about the film and had thrown it away the day before. Hard to say what was in the cans. There might have been a print of Hats Off. Too bad we’ll never know.

7. Anything else you want to say?

The last time I showed films at the Roxy Theater in SF I saw that they still used carbon arcs. I hope they still do. I would imagine there are a few more places in the United States clinging to the old technology.

When I owned my own theaters I would occasionally project nitrate for a very lucky few. The last time I did that was at a theater I cannot name where I did a day of “secret cinema.” It’s too bad we couldn’t spell out just how really secret it was. The last time one of my nitrate prints was publicly screened was by accident. It was an event at a theater doing a program of old films projected with live music accompaniment. I had provided twenty minutes of 35mm and forty minutes of 16mm for the show. The people putting it on really liked the 35mm material better. I was in Europe showing films at the time, so a friend who had a key to my film storage let them in to grab some more 35mm.

Later I heard from someone who had been to the show who told me that she had loved one of the films. I asked which one. I was told “The boxing one, it looked so beautiful.” Wow, the only boxing film I had was a nitrate original ten minute short. Just by luck it was one that was grabbed and projected. Luckily, no one was hurt.

———————————————————————————————————————————————————–

The National Film Preservation Foundation is the independent, nonprofit organization created by the U.S. Congress to help save America’s film heritage. They work directly with archives to rescue endangered films that will not survive without public support.

The NFPF will give away 4 DVD sets as thank-you gifts to blogathon donors chosen in a random drawing: Treasures III: Social Issues in American Film, 1900-1934 and Treasures IV: American Avant Garde Film, 1947-1986.

Here’s where you can give generously to the National Film Preservation Foundation.

9 responses so far ↓

1 The Siren // Feb 13, 2010 at 8:29 pm

What a great way to kick off this blogathon. Absolutely fascinating, and very educational for me. To my regret, and evident loss, I don’t think I have seen a nitrate print projected.

2 Marilyn Ferdinand // Feb 14, 2010 at 10:44 am

This is a FANTASTIC post and very educational.

I used to run a carbon arc follow spot in high school. I guess our school thought it was safe enough in the 1970s. They replaced it, of course, with electric light soon enough.

3 Joe Thompson // Feb 14, 2010 at 10:56 pm

Thank you for Dennis Nyback’s nitrate stories. I remember San Francisco theaters with carbon arc lamps — I assume they were carbon arcs because the quality of the light was different. Your mention of film getting stuck brought back sad memories of my super-8 mm safety films getting jammed, turning brown, and melting.

4 Kassy // Feb 15, 2010 at 1:02 am

That was absolutely amazing, thank you so much!!!

5 Flickhead // Feb 15, 2010 at 6:54 am

Anne, that’s an interesting interview. I love the part about the projection booth shutting down to contain the fire — and the projectionist!

I know what he means when he talks about carbon arcs. I worked with carbon arcs for twenty years in printing before they were outlawed in New York State. You could go blind looking into them for just a few seconds. At the time I never gave thought to the air I was breathing, full of carbon dust.

6 Jacqueline T Lynch // Feb 16, 2010 at 2:04 pm

“It is the difference between a Vermeer and a jigsaw puzzle.”

Oh, wow, this was a great piece. Thanks so much for this splendid interview.

7 Tinky Weisblat // Feb 18, 2010 at 1:11 pm

I loved this interview; it put together lots of pieces of information I ALMOST knew very clearly and concisely. Thanks to you and to Dennis Nyback.

8 Ferdy on Films // Feb 24, 2010 at 5:58 am

[...] essential blog The Self-Styled Siren. Anne Richardson of Oregon Movies, A to Z has a fascinating interview with Oregon projectionist Dennis Nyback on what it was like to project nitrate film. The tech geek [...]

9 Dave // Sep 14, 2010 at 12:22 pm

I worked at the Venus Theater as a projectionist in Winnfield, LA in 1969 – 1970. We used carbon arcs for lighting and had the same sort of fire system with drop down metal plates over the view ports and heavy metal doors. We always heard stories of nitrate files fires and explosions, but to my knowledge we only had safety film. Sadly, the Venus closed in 1970 and was recently tron down.

Leave a Comment