April 24th, 2014 by Anne Richardson · Uncategorized

I took Oregon Movies, A to Z down today.

Bo togel yang menawarkan Bo Togel Hadiah 2d 200rb menjadi salah satu pilihan paling dicari oleh para pemain togel online. Dengan hadiah besar ini, pemain bisa memperoleh keuntungan maksimal hanya dengan memilih angka yang tepat. Platform yang menawarkan hadiah ini biasanya dikenal dengan keamanan transaksi yang terjamin.

Yesterday I attended the mini-ceremony welcoming James Blue’s papers and films to the University of Oregon’s Knight Library.

Pengalaman bermain kartu kini bisa dinikmati dari rumah tanpa harus pergi ke kasino. Situs poker menghadirkan berbagai varian permainan yang bisa disesuaikan dengan keinginan pemain. Antarmuka yang intuitif membuatnya mudah diakses oleh siapa saja, baik pemula maupun profesional. Ini menjadi alasan utama mengapa permainan ini semakin populer di kalangan masyarakat.

When I started Oregon Movies, A to Z, I was alarmed that no one was paying attention to Oregon’s film history. I no longer have that feeling. James Fox, the head of Special Collections at Knight Library, has collected the papers of three Oregonians who made significant contributions to American film history: James Ivory, Ken Kesey and James Blue. The Cinema Studies department faculty were present and fully engaged in celebrating the acquisition of James Blue’s papers and films.

Banyak anggota dan bettor Bandar Togel kami yang telah meraih kemenangan terbesar ketika bermain di salah satu dari 10 situs togel terpercaya 2024 kami, yang dikenal sebagai agen judi togel terpercaya online 24 jam. Situs-situs ini menawarkan berbagai fasilitas yang sangat lengkap di seluruh dunia.

Oregon Movies, A to Z is no longer needed.

Beberapa Slot Online gacor menawarkan fitur jackpot tetap yang memberikan hadiah besar secara teratur kepada pemain yang beruntung.

I will continue advocating for support for Oregon film history scholarship. I want to see one of the Oregon University System schools choose to develop a specialty in animation studies, including animation history, and for that school to begin a scholarly collection of books on that subject. It is not possible today to research Oregon’s animation history with the teachers and the library resources we currently possess. I am interested in changing this.

If we have world class artists, we should have world class scholars.

Sebagai salah satu pasaran terpopuler, Toto Macau menawarkan berbagai jenis taruhan dengan hadiah besar. Sistem yang aman dan transparan membuat Toto Macau menjadi pilihan utama bagi pemain profesional. Jangan lupa cek angka keberuntungan Anda di Toto Macau hari ini untuk kesempatan menang besar.

Speaking of which, thank you to the people who wrote in with information which helped deepen my understanding of Oregon film history!

Mengakses data HK setiap hari menjadi rutinitas penting bagi pemain setia togel Hongkong yang ingin meningkatkan peluang menang. Dengan mempelajari keluaran HK, pemain dapat mengidentifikasi pola-pola tertentu yang sering muncul. Hasil pengeluaran HK ini kemudian digunakan sebagai dasar untuk memprediksi angka di togel HK. Dengan strategi ini, mereka bisa bermain lebih percaya diri di togel hari ini dan meraih kemenangan di HK hari ini.

AR

Tags:

February 12th, 2014 by Anne Richardson · Handy guide series

Police face off against antiwar demonstrators in The Seventh Day, a 1970 documentary shot by Portland State University students.

A long list of American filmmakers have chosen The City as a subject in documentaries, educational films, and narrative features. The following list is of films/filmmakers with an Oregon connection.

This list includes both fiction and non-fiction films. It is NOT comprehensive!

The Boy Mayor 1914, directed by Henry McRae. Starring teenager Eugene J. Rich, Portland’s real Boy Mayor. The fictional plot line depicts the “clean up the streets” motive behind the Boy Mayor campaign. Restored by National Film Preservation Foundation, thanks to Michele Kribs, Oregon Historical Society’s film archivist. Shot in Los Angeles.

Dementia 1953, retitled Daughter of Horror 1955, directed by John Parker, Jr. The City is a moody, expressionist dreamscape in this combination art film/horror film made by the son of Portland theater chain owner, J. J. Parker. Score by George Antheil. Shot in Los Angeles.

Portland Expose 1957, directed by Harold Schuster. Exploitation film, based on real events. The plot line had to be fictionalized so it could be believed. In real life, it was a well known crime boss, not an upstanding small businessman, who blew the whistle on the corrupt union leader who was muscling in on his vice world territory. Shot in Portland.

The Olive Trees Of Justice 1962, directed by James Blue. Banks of barbed wire surround buildings, police are everywhere, bombs go off, tanks roll by, and yet somehow everyday life still goes on. A young French colonialist tries to locate his childhood friends, and his own identity, in the middle of the chaos. Shot in Algiers.

The Seventh Day 1970, directed by students at PSU’s Center For The Moving Image. Documentary coverage of an anti-war demonstration which erupts into violence. Made by Tjeck Dusseldorp, with Charles Auch and future music video superstar Jim Blashfield. Shot in Portland.

We Are The City 1972, directed by Tom Chamberlin. Portland is never named in this educational film, made for Encyclopedia Britannica. Includes Mayor Terry Shrunk and Neil Goldschimdt (another Boy Mayor, but at that time still a City Councilman). The footage is 95% Portland.

The Case Of The Kitchen Killer 1976, directed by Tim Smith. Self taught 16mm filmmaker’s black comedy uses Portland locations sensitively. Smith was just out of high school when he made this film. The hand of crew member Matt Groening makes a cameo appearance holding a murder weapon. Ben Padrow provides the voice over narration. Shot in Portland.

Who Killed Fourth Ward? (1976-77) and The Invisible City: Houston Housing Crisis (1978-79), directed by James Blue. Oregon’s first Oscar nominee focused on urban housing conditions for his two longest docs, made for Houston public television. Shot in Houston.

Property 1977, directed by Penny Allen. Eight Portland friends respond to gentrification by deciding to band together to buy a house in their Lair Hill neighborhood. Not a documentary, but inspired by real life events, with some of the participants in the real events joining the cast, playing themselves. Cinematography by Eric Ericson, sound by Gus Van Sant. Shot in Portland.

Mahagonny 1980, directed by Harry Smith. “(Smith’s) cinematic transformation of Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht’s caustically satirical opera is an allegory that explores human needs and desires amid the rituals of daily life in New York City. The film is a collage composed from a variety of film genres, intercutting portraits of important avant-garde figures, New York City landmarks, and Smith’s visionary animation.” Shot in New York.

Talk Radio 1988, directed by Oliver Stone. Based on a play written by Portland artist Tad Savinar and New York actor Eric Bogosian. The play is about urban discontent, but the real reason the movie Talk Radio is on this list is that Savinar combines his career as a fine artist with his career as an urban designer. Currently he is Vice Chair of the Portland Design Review Commission. Shot in Dallas.

Drugstore Cowboy 1989, directed by Gus Van Sant. The fictionalized memoir of a real life felon provides a portrait of a city. Shot as a period piece, set in the 1970’s. Starring Matt Dillon, Kelly Lynch and William Burroughs. Van Sant’s ascension to stardom branded Portland as an indie capital. Shot in Portland.

Portlandia 2011 – 2018, directed by Jonathan Krisel. Writer-producer-stars Carrie Brownstein & Fred Armisen, plus producer David Cress. Award winning television series sending up Portland’s middle brow quirkiness. Shot in Portland.

Alien Boy 2012, directed by Brian Lindstrom. Documentary examining Portland’s response to the death of James Chasse, Jr., who died in police custody. Shot in Portland.

Tags: Brian Lindstrom·Charles Auch·Eric Bogosian·Eric Ericson·Eugene J. RIch·Gus Van Sant·Harold Schuster·Henry McRae·James Blue·James Chasse Jr·Jim Blashfield·Kelly Lynch·Matt Dillon·Matt Groening·Michele Kribs·Neil Goldschimdt·Oliver Stone·Penny Allen·Tad Savinar·Terry Shrunk·Tim Smith·Tjeck Dusseldorp·Tom Chamberlin·William Burroughs

Irene Bedard, as Indian Jenny

Who was it that said a movie only needs three good scenes?

Paul Newman experimented with that formula in 1970 by making a film with only one. In Sometimes A Great Notion, Richard Jaeckel played the trusting, loyal Joe Ben who drowns as his cousin Hank tries and fails to keep him alive. Jaeckel was Oscar nominated for a performance which culminates in that one scene, but what happened to the rest of Kesey’s masterful epic?

Where are the other two good scenes?

I am guessing they landed on the cutting room floor when actor-producer-director Paul Newman jettisoned the novel’s main plot. A second try at adapting Kesey’s sprawling masterpiece, using the multi episode format available in the television mini series, could restore the “since you slept with my mother, I am going to sleep with your wife” plot line which is central to the book.

So invested am I in the belief that Sometimes A Great Notion would make an excellent mini series that I have gone to the trouble of assembling a dream cast.

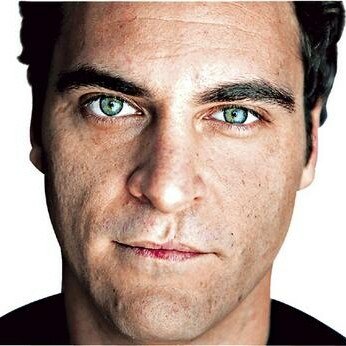

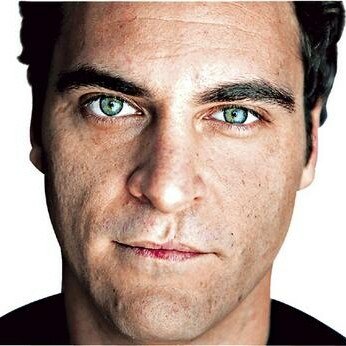

Joaquin Phoenix, as Hank Stamper

It is clear that Hank Stamper would best be played by Joaquin Phoenix. Joaquin matches Kesey’s description of Hank, down to the curly hair, muscular build and flashing green eyes. Hank has a high intelligence, a volatile temper and a secret which he keeps from everyone, including his wife, and including himself.

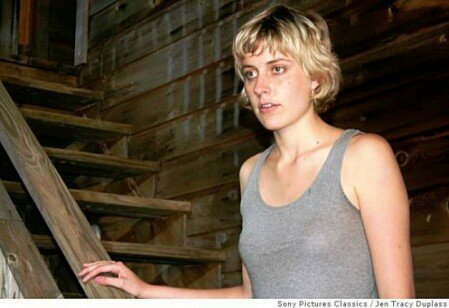

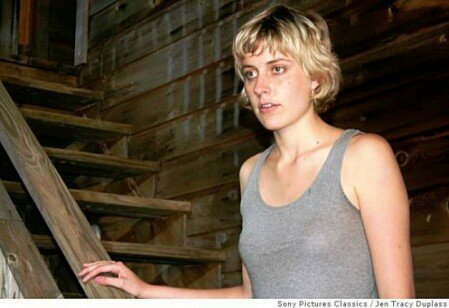

Greta Gerwig, as Myra Stamper

Myra, Henry Stamper’s second wife, seduced her stepson Hank on his sixteenth birthday, and slept with him throughout his high school years. She treats Hank as her lover even after she returns to the East Coast to raise Lee, Hank’s half brother, in privilege. When Myra, isolated by her transgression, commits suicide, Lee drops out of graduate school to take revenge. He goes West to seduce Hank’s wife, and ruin his life. However when he meets Viv Stamper, he falls instantly, genuinely, in love. But he still makes sure Hank witnesses him in bed with Viv just as he, Lee, as a child, had witnessed Hank in bed with Myra. Viv leaves Hank, but Lee remains behind. Alone in the bus station, waiting to get out of town, Viv sees a photo of young Myra, who she closely resembles. Viv understands for the first time that she was always, to Hank, only a substitute.

That’s the plot of Sometimes A Great Notion. There’s logging, the union, bar fights, prostitutes, and death. But the real story is three generations of sexual obsession.

The Stamper family is driven by ghosts. They are possessed by them, in bondage to them. Monstrous in their strength, their hatred and their self definition, they are shadow people in thrall to the past. The community, not incorrectly, perceives them as a threat. Lee, who was raised elsewhere, returns intending to destroy his family but instead joins them. Viv, who married into the family, and had no idea of leaving, escapes. There is no room for women in the world of the Stamper family. Kesey knew this about Viv, and described her in his notes as “just an ordinary girl, caught up in a family plot”.

Greta Gerwig, as Viv Stamper

Greta Gerwig has the range to play the dual roles of exotic, neurotic, sex abusing Myra Stamper, and the normal, ‘ordinary girl’ Viv Stamper. She has the power to play both. As Kesey wrote: “Viv is a pawn in a game, a long ago game”.

Then there’s Lee.

In Kesey’s notes for the novel he writes: “Hank the fighter, the winner. Lee the pacifist, the loser.

When Kesey wrote Sometimes A Great Notion, jocks were winners. Much of the plot concerns the courage the lanky, underdeveloped Lee must summon to continue seducing the wife of his violent, physically powerful half brother. The better Lee knows Hank, the more he realizes how dangerous his plan is.

How to cast this role?

The most important qualities Lee must have are a physical resemblance to Hank Stamper/Joaquin Phoenix, and the ability to transform from child to adult. He must be, as all Stampers are, convincingly, and passionately self deluded.

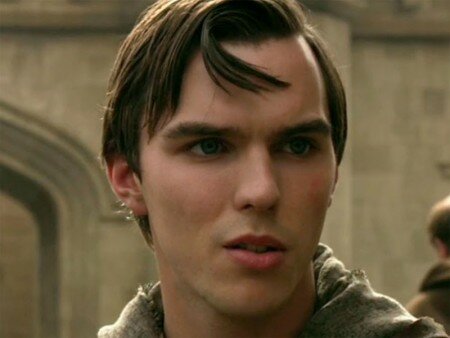

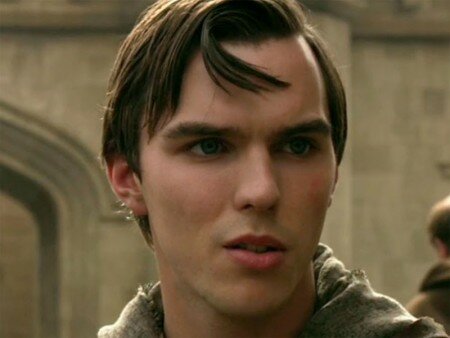

Nicholas Hoult, as Lee Stamper

When Lee chooses to remain behind with Hank, the brother he both loves and hates, we understand he has chosen death. He had his chance at life. Viv=vitality=life. As Viv watches the two men struggle to bring the logs down the river from the window of her Greyhound bus out of town, she is Ishmael escaping the unholy vortex of Moby Dick. Kesey’s understanding of Viv as a whole person, not a plot device, is entirely, but entirely, absent from the 1970 film adaptation of Sometimes A Great Notion.

So many other wonderful character parts! Ancient patriarch Henry Stamper should be played by an actor who is old, old, old enough to be a grinning defiant skeleton. Death in a hardhat. Terrifying! That’s the way Kesey wrote him. Then there’s obsequious undertaker Boney Stokes, apoplectic union man Floyd Evenwrite, ice cold bureaucrat Jonathan Draeger, and hard living, mud flat dwelling, fortune telling Indian Jenny, who spends her entire life in love with her memory of the handsome green-eyed logger, Henry Stamper, who alone among all his peers refused to patronize her services. Kesey wrote an entire world.

One appreciative reader: We have here all you could ever want to know about felling trees, bear hunting, the life and language of a small-town bar, juvenile delinquents in small-town America, music of the 50s and 60s, shamans, Indians, evangelists, Captain Marvel, small-town justice, union organizing, revenge, old age, dying, death.

Irene Bedard, as Indian Jenny

Restoring Indian Jenny to the plot would make an honest miniseries out of a Sometimes A Great Notion, and communicate both the novel’s social and psychological complexity, and its epic sweep. I propose Irene Bedard to play the beautiful small town prostitute who falls in love with the young logger Henry Stamper, and whose thwarted union with him provides the narrative engine for the rest of the plot.

It is because of Henry’s unexpressed love for Indian Jenny that he marries socialite Myra, who has Indian Jenny’s long black hair. It is because of Henry’s son Hank’s incompletely expressed, semi-incestuous love for Myra that he marries Viv, who has Myra’s face. I calculate it would take five to six one hour episodes to do justice to this multi generational chain of human frailty masquerading as strength.

I have done the casting.

Who will make Sometimes A Great Notion: The Mini Series?

Tags: Greta Gerwig·Irene Bedard·Joaquin Phoenix·Ken Kesey·Nicholas Hoult·Paul Newman·Richard Jaeckel

November 15th, 2013 by Anne Richardson · News

Not all Oregon film historians are women, but this first group was. Left to right: Heather Petrocelli, Anne Richardson, Ellen Thomas, Rose Bond. Not pictured: Michele Kribs, unavailable because she was out riding her motorcycle.

Dateline: 2033, 20 years from now.

The Oregon Film History Initiative celebrated its 20th birthday today by blowing out candles on 20 virtual cakes scattered throughout the state.

Founded in 2013 by a group of librarians and historians, OFHI’s original mission was to ensure that key documents and artifacts essential to a full understanding Oregon’s unique film history were successfully archived within the state.

The Initiative began unofficially with the acquisition of James Ivory’s papers at the U of O. A trickle of film scholarship triggered by Richard Herskowitz’s 2013 James Blue Tribute turned into a steady stream. Portland’s silent film industry, Oregon’s McCarthy era Westerns, Godard’s trip through the Pacific Northwest with Jon Jost in 1972 – books on these subjects transformed public understanding of the intersection between Oregon film history and American film history.

Few can remember the time before a full length biography of Portland musician Melvin Jerome Blank, aka Mel Blanc, radically re-positioned pre-Portlandia Jazz Age Portland as an engine of American pop culture, and launched a new cultural tourism industry.

Oregon Film History Initiative brought together a truly diverse set of stakeholders. While UO collected papers of Oregon filmmakers, Oregon Heritage Commission, in cooperation with Travel Oregon and Oregon Cultural Trust, supported the restoration of downtown theaters in rural Oregon towns.

NWFC continued their trademark events. Lewis & Clark began a media literacy summer school for teachers. UO, working in partnership with Oregon Cartoon Institute, began hosting an annual Oregon film history conference. OCI secured a digital humanities grant to tell the story of Lew Cook, Homer Groening, and Frank Hood, three WWII vets whose passion for 16mm filmmaking would re-ignite Portland’s independent film scene.

Meanwhile, the Initiative’s popular annual fundraisers provide homesick Oregon film artists in LA and NY an annual reason to fly home for a visit.

Virtual candles for the 20th birthday celebration were blown out in Salem, Astoria, Eugene, Pendleton, Cottage Grove, Joseph, Grants Pass, Bend, Baker, Klamath Falls, Jacksonville, Oregon City, McMinnville, Sandy, Brownsville, Corvallis, and all four quadrants of the city of Portland.

Tags: Ellen Thomas·Frank Hood·Heather Petrocelli·Homer Groening·James Blue·James Ivory·Jean Luc Godard·Jon Jost·Lew Cook·Mel Blanc·Michele Kribs·Richard Herskowitz·Rose Bond

October 6th, 2013 by Anne Richardson · Oregon animator

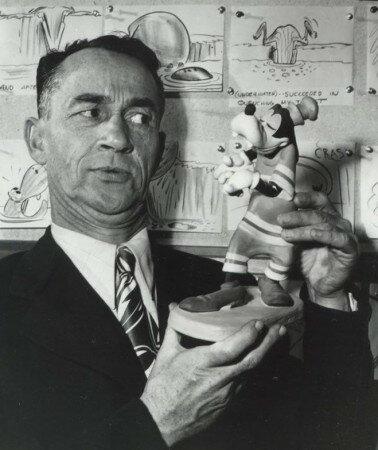

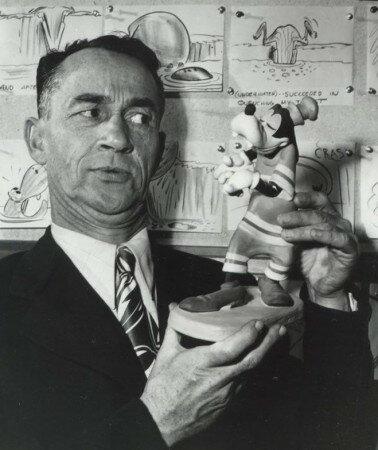

Vance DeBar “Pinto” Colvig, with Goofy

Pinto Colvig may be the first Oregon animator.

Inspired by the commercial and artistic success of Oregon cartoonist Homer Davenport (1867-1912), Pinto Colvig began by cartooning for newspapers. He moved from cartooning to animation, a transition Homer Davenport would have made if he had lived long enough. Only five frames survive of Pinto Colvig’s 35mm feature length animated film, Creation, made in San Francisco in 1915.

That’s the year D. W. Griffith made Birth Of A Nation.

That’s the very sunrise of cinema.

On October 12, Oregon Cartoon Institute and Portland ASIFA partner up to bring Medford historian Ben Truwe to Portland to tell us more about this forefather of Oregon animation and cartooning.

The following timeline is taken from Ben Truwe’s webpage about Pinto Colvig.

1892 Born in Jacksonville, Oregon

1899 Dances the cakewalk on Jacksonville stage

1905 Performs as a musical clown on the street in Portland during the Lewis & Clark Exposition

1906 Fails admission exam for high school, instead hangs out with Frank Willeke, the Medford Main Street railroad flagman, whose voice and personality he would later adapt for the character Goofy

1910 Enrolls at Oregon Agricultural College (now OSU) in Corvallis

1915 Directs the early (some say the first) feature length animated film Creation (lost film) in San Francisco

1919 Directs early color animated film Pinto’s Prizma Comedy Revue (lost film) in San Francisco

1930 Begins working as a writer for Walt Disney

1932 Voices Goofy in The Whoopee Party, continues to voice Goofy for decades

1937 Voices Sleepy and Grumpy in Snow White

1939 Voices Gabby in Gulliver’s Travels

1946 Voices Bozo the Clown for Capitol Records, records which make more money than God

1967 Dies in Los Angeles

Here’s how much Walt Disney admired Pinto Colvig – he modelled his official Walt Disney logo after Pinto’s own rounded signature, which you can see below.

Ben Truwe will illustrate his talk with film clips and photos, and will read an excerpt from Pinto’s unpublished autobiography. Bring your questions – Oregon Cartoon Institute believes in audience Q & A.

More About Goofy: Pinto Colvig, Oregon Animation Pioneer is presented by Portland ASIFA and Oregon Cartoon Institute The evening is free for members of Portland ASIFA and for students. For non-members and non-students, admission is $3.00.

More About Goofy: Pinto Colvig, Oregon Animation Pioneer takes place at 5th Avenue Cinema, 510 SW Hall Street, Portland, Oregon at 7:00 PM on October 12.

On Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/events/234922229992860/

Tags: D. W. Griffith·Don Livingston·Fleischer Brothers·Homer Davenport·Pinto Colvig·Vance DeBar"Pinto" Colvig·Walt Disney·Walter Lantz

Four years after Douglas Engelbart (1925 – 2013) invented the computer mouse, he sat down to demonstrate it to 1,000 of his closest friends. Because he was from Oregon, and thinking this way comes naturally to us, he made sure his 90 minute presentation was captured on video.

From his NY Times obituary:

For the event he sat on stage in front of a mouse, a keyboard and other controls and projected the computer display on a 22-foot-high video screen behind him. In little more than an hour he showed how a networked, interactive computing system would allow information to be shared rapidly among collaborating scientists. He demonstrated how a mouse, which he had invented just four years earlier, could be used to control a computer. He demonstrated text editing, video conferencing, hypertext and windowing.

You can see the entire presentation on Youtube. Here’s the Youtube description.

On December 9, 1968, Douglas C. Engelbart and the group of 17 researchers working with him in the Augmentation Research Center at Stanford Research Institute in Menlo Park, CA, presented a 90-minute live public demonstration of the online system, NLS, they had been working on since 1962. The public presentation was a session in the of the Fall Joint Computer Conference held at the Convention Center in San Francisco, and it was attended by about 1,000 computer professionals. This was the public debut of the computer mouse. But the mouse was only one of many innovations demonstrated that day, including hypertext, object addressing and dynamic file linking, as well as shared-screen collaboration involving two persons at different sites communicating over a network with audio and video interface.

I hereby claim Douglas Engelbart: The Mother Of All Demos as an Oregon film, on the basis of Oregonian Douglas Engelbart’s contribution as producer, director, writer and star.

Tags: Douglas Engelbart

James Chasse lived independently with severe and persistent mental illness in downtown Portland. On Sept. 17, 2007, he died in the custody of Portland police.

The sound of the impact of two bodies crashing against pavement attracted the attention of diners at Bluehour. Autopsy revealed that 16 of James Chasse’ ribs had been fractured. Was it from the weight of police officer Christopher Humphreys? Or could it have been the punches and kicks, witnessed by the horrified diners, which he received once he was down?

Tasered and hog tied, Chasse lay in a pool of his own blood while cops and medics wrote up the incident. They described him to bystanders as a drug using transient with a police record. Chasse was thin and filthy, but he had no drugs in his system nor in his possession. He had no police record.

Nevertheless, in his report Officer Humphreys faithfully recorded what his imagination told him about the bleeding man hogtied at his feet. Who would object if he entered the word “transient” where he could have entered the address plainly stated on Chasse’s ID? As it turns out, Chasse’s parents took exception to having their son beaten to death in broad daylight and took the City of Portland to court.

Brian Lindstrom’s approach as a documentarian has always been to use his camera to amplify the voices of people we ignore, a self effacing tactic which showcases his ability to listen, not to speak. In Kicking and Finding Normal, he focused on people struggling with substance abuse. In Pay My Way With Stories, he followed students in a writing workshop for at risk teens. His focus was always on his subject, not on his reaction to his subject. Embracing the stripped down visual aesthetic of cinema verite, he was attentive, patient, and heroically compassionate, if a little emotionally remote.

In Alien Boy, he steps away from all that. His fury animates every frame.

Lavishly made, Alien Boy is a visually sumptuous, riveting narrative. For the first time, Lindstrom does not lead with his compassionate heart. He leads with his eye. A very smart choice. The filmmaking is so strong that by the time (3/4 of the way in) you are watching the video surveillance footage – shot by one of those Orwellian overhead cameras in the police station – of the moments when Chasse, still hog tied and close to death, begs for water, you are in too deep to turn away. Alien Boy is a horror film in that sense.

Brian Lindstrom is furious that James Chasse died at the hands of Portland police. But he doesn’t romanticize his fury. Too canny for that! Instead, he prioritizes the storytelling. Is it possible to make a film in which a grieving mother’s tearful halting narrative is not the most heartbreaking primary source material? Grief, yes. Facts, yes. Lies, yes. Poetry (written by Chasse), yes. Lindstrom shows us everything. Stylistically, it is a tour de force.

Such focus. Such discipline!

Brian Lindstrom spent the six years which have passed since James Chasse died making a film which tells that story so powerfully it will be seen around the world. In Alien Boy, he comes into his own as an artist.

I hereby claim Alien Boy as an Oregon film, on the basis of every possible qualifying criteria.

Director: Brian Lindstrom. Cinematographer: John Campbell. Score: Charlie Campbell. Writer: Matt Davis. Editor: Brian Lindstrom. Asst. Editor: Andrew Saunderson. Animation: Andrew Saunderson. Producer: Jason Renaud.

Cast:

Randy Moe, Brian Lee, Steve Doughton, Mike Lastra, Eva Lake, Marian Drake, Betty Mayther, Rozz Rezbeck, Sam Henry, Michael Brophy, Brian Wasserman, Odette Dunbar, Yvonne Ingram, Russell Sacco, Richard Elliot, all James Chasse’s friends.

Linda Gerber and James Chasse, Sr. – James Chasse’s parents

Constance Doolan, Randall Stuart, Jamie Marquez, David Lillegaard – eyewitnesses

Matthew Charles Davis – Portland Mercury

Anna Griffin – The Oregonian

Karen Gunson, MD – Multnomah County Medical Examiner

Scott Westerman – Portland Police Association president

Tom Steenson – Chasse family attorney

Bob Joondeph – Disability Rights Oregon

Dan Handelman – Portland Copwatch

Karl Brimner – Director, Multnomah County Mental Health

Sam Adams – Mayor of Portland

Ted Wheeler – Multnomah County Commission chair

Alien Boy screens Feb. 24 – Mar. 7 at Cinema 21 in Portland, Oregon.

Tags: Andrew Saunderson·Brian Lindstrom·Charlie Campbell·Christopher Humphreys·James Chasse Jr·Jason Renaud·John Campbell·Matt Davis

December 30th, 2012 by Anne Richardson · News

I am still thinking about Camille A. Brown’s Mr. TOL E. RAncE, performed in Portland earlier this month. My essay below, written in 2005, addresses the American performance tradition which Brown examines, critiques, celebrates, discards and transcends.

Thirteen Ways Of Looking At Blackface

Acting on the principle that if you can’t say anything nice, don’t say anything at all, many books of American theater history either make no mention of blackface minstrelsy, or include a brief discussion focusing mostly on how deeply horrified the author is by the information he/she is about to convey.

If this policy was intended to help blackface go away, it didn’t work. It never would work. Blackface, and the influence of blackface, is everywhere. With a tip of the hat to Wallace Stevens, here are thirteen ways to view the long, vexing, love affair our country has with cross racial impersonation.

1. Blackface is Evil

Bill Robinson compares notes with Shirley Temple in THE LITTLEST REBEL (1935).

“What does that mean – “free the slaves”?“ Shirley Temple asks Bill Robinson, a wise old man in formal dress who happens to be her own personal property. “I don’t know what it means myself.” he replies thoughtfully.

The clues that the South these two inhabit exists solely in the minds of white Northern show business professionals are all over THE LITTLEST REBEL: from the blackface Shirley later puts on, to the banjo Robinson plays while Shirley sings Polly Wolly Doodle, to Zip Coon, the tune with which Robinson entertains Shirley’s birthday party guests.

Zip Coon was introduced by pioneering solo blackface entertainer George Washington Dixon in 1829. A tsunami sized hit whose popularity presaged the minstrel craze yet to come, today we know it as Turkey In The Straw.

2. Blackface is Essential

Judy Garland sings Under The Bamboo Tree with Margaret O’Brien in MEET ME IN ST. LOUIS (1944)

Hollywood didn’t make a musical which included an actual turn-of-the-century coon song. However, in MEET ME IN ST. LOUIS, Judy Garland sings the best selling song three African American geniuses created in deliberate response to that craze.

Written by three of the most talented, disciplined, and ambitious artists ever to turn their attention to the creation of pop, Under The Bamboo Tree was the product of Robert Cole, the writer-director-producer-star of the first all black musical, A Trip To Coontown; J. Rosamond Johnson, the composer of Lift Every Voice & Sing, the black national anthem; and James Weldon Johnson, the author of The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man.

They constructed Under The Bamboo Tree to cater to the nationwide fad for dialect songs, while steering clear of negative racial cliches. The commercial and artistic successes they enjoyed as a team helped pave the way for both Tin Pan Alley and the Harlem Renaissance.

3. Blackface is Benign

Jimmy Stewart and Donna Reed sing Buffalo Gals in IT’S A WONDERFUL LIFE (1946)

The song Jimmy Stewart sings with Donna Reed on the way home from a high school dance, just before she accidentally loses her robe and jumps into a Bedford Falls rosebush, was originally intended to both express and lampoon the powerful allure of Buffalo, New York prostitutes to the men who worked the Erie Canal.

Buffalo Gals was copyrighted to Cool White, one the first minstrel superstars. Some of its many variants (Bowery Gals, Alabama Gals, Darktown Gals, etc.) testify to an alternate reading of “buffalo” as a coded reference to “African American”, as seen in the term “buffalo soldiers”. Whether the song was inspired by prostitutes from Buffalo, or by prostitutes who were coded as “buffalo”, nothing is left of its minstrel past in the sanitized lyrics we now know.

4. Blackface is Pathetic

Fred Astaire brings Dixie to Paris with Kay Thompson in FUNNY FACE (1957)

Fred Astaire and Kay Thompson are spiritually, if not actually, blacked up when they sing Clap Yo Hands in a Parisian salon filled with bored intellectuals. Minstrelsy is the flag they wave to set themselves apart from the Old World ennui which envelopes everyone else in the room.

In their hands “Why does a chicken cross the road?”, the oldest of minstrel show jokes, is an act of patriotism. But the Parisians were right to yawn. Even two show business pros can’t revive this corpse. What you learn from FUNNY FACE is that beatniks had their own link to minstrelsy – the tambourine. And that Michael Jackson definitely stole his look, especially his socks, from Astaire’s wardrobe.

5. Blackface is Angry

Ossie Davis directs Mabel Thompson as the militant, strip teasing Topsy in COTTON COMES TO HARLEM (1970)

She comes onto the stage, doubled over, wearing rags, with a bandanna on her head. By the end of the song she is triumphantly naked, except for a few strategically placed balls of cotton. The mood of Mabel Thompson’s dance is defiant. She is defeating slavery, defeating cotton, defeating history.

The crowd roars in delight when she takes off her bandanna to reveal a multi-braided Topsy hairdo, and roars again in approval when she lifts off the Topsy wig to reveal her own natural hair.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the most popular stage play of the nineteenth century, provided multiple opportunities for blackface. Uncle Tom was played in blackface. So was Topsy. Ossie Davis uses this history in Cotton Comes To Harlem - in several ways.

6. Blackface is Haunted

Gary Cooper sings Sweet Genevieve with his six bachelor housemates in BALL OF FIRE (1941)

Not all minstrelsy was clowning. You went to cry as much as to laugh. Woodman, Spare That Tree kept minstrel show audiences weeping for decades, as did Silver Threads Among The Gold. Victorian Americans may have kept their emotions under control elsewhere, but once they were inside the minstrel hall, they cried their eyes out. They cried for Old Black Joe when he was in slavery, they cried for him during the war, and they cried for him after the war. When they got tired of crying over Joe, they pined for long ago girlfriends (Sweet Genevieve) or dead ones (Jeannie With The Light Brown Hair).

In this scene, Cooper’s posse of aging bookworms toasts love with a wine addled sing along. Minstrelsy was born amidst beer, so it is appropriate that these nutty professors would be boozing it while they close harmonize a wistful old minstrel tune.

7. Blackface is Political

Brian De Palma turns the tables in the Be Black, Baby sequence in HI MOM (1970).

In HI MOM, Robert De Niro brilliantly interrogates a mop. “What’s that? Make love, not war? I make love very well, thank you very much!” he screams. He is auditioning for an acting job, and he gets it. He plays a white cop in Be Black, Baby, an Off Off Broadway play in which black actors in whiteface invite white playgoers to share the black experience by having their wallets taken and their women sexually violated, followed by wrongful arrest. They also get blacked up.

If you think you fully understand the power politics behind cross racial impersonation, and do not think you could possibly be shocked by anything De Palma has to say, see HI MOM.

8. Blackface is Over

Duke Ellington passes Freeman Gosden and Charles Correll by in CHECK & DOUBLE CHECK (1930)

The dapper Duke gives a quizzical look to two shabbily dressed white men wearing blackface as he heads past them into a brightly lit mansion where he and his band have been hired to play a sumptuous party. This moment marks an historic changing of the guard, when African American entertainers sans blackface left white blackface entertainers in the dust.

CHECK & DOUBLE CHECK is the first and last film in which you can see Freeman Gosden and Charles Correll, the white actors who created AMOS ‘N’ ANDY. Duke Ellington would go on to appear in eight Hollywood films, never in blackface, always as himself.

9. Blackface is Current

Andy Samberg and Chris Parnell cruise for cupcakes in LAZY SUNDAY (2005)

The best possible proof that cross racial impersonation is still with us as a national obsession is the instant success of Andy Samberg and Chris Parnell’s rap parody, LAZY SUNDAY. Downloaded by millions and sent around the world minutes after airing on Saturday Night Live, LAZY SUNDAY inspired a string of online homage parodies, the best of which ends with two nice Jewish boys bringing home a menorah.

(I wrote this list in 2005. Andy Samberg didn’t rest on his laurels. His Iran So Far is a comprehensive lexicon of minstrel tropes. See it to believe it!)

10. Blackface is Sublime

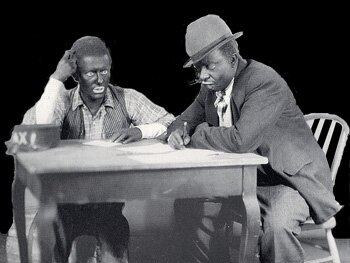

Tim Moore in a tutu smoking a cigar in BOY WHAT A GIRL (1947).

There is no blackface in BOY WHAT A GIRL.

However there is cross dressing, and cross gender impersonation was second only to cross racial impersonation on the list of transgressive thrills offered the Victorian audiences of the minstrel show. The incomparable Tim Moore carries on this performance tradition in BOY WHAT A GIRL, as have, more recently, both Martin Lawrence and Tyler Perry.

11. Blackface is Tasteless

Ben Stiller blacks up in ZOOLANDER (2001)

With an Irish mom in show business and a Jewish dad in show business, Ben Stiller’s credentials are impeccable for blacking up. Irish performers dominated the minstrel industry for most of the nineteenth century, Jewish ones brought it into the the twentieth. George M. Cohan, Eddie Cantor and Al Jolsen all practiced “white out of black”, as does Ben Stiller in ZOOLANDER.

12. Blackface is Enigmatic

Cliff Edwards sings When You Wish Upon A Star in PINOCCHIO (1940)

Minstrel shows no longer drew crowds when Cliff Edwards began his career in the 1920’s, but blackface still secured individual performers license to be more emotional, more theatrical, more unpredictable than they could be without it. Edwards made his name playing the ukelele and singing in blackface. By the time he supplied the voice for Walt Disney’s Jiminy Cricket, blackface was no longer part of his public persona. It is, however, where he began.

13. Blackface is Our Inheritance

Bert Williams plays cards in NATURAL BORN GAMBLER (1916); Eddie Cantor runs away from Ethel Shutta in WHOOPEE (1930); Mae West checks George Raft’s hat in NIGHT AFTER NIGHT (1932)

NATURAL BORN GAMBLER provides film record of Bert Williams’ blackface. WHOOPEE does the same for his Ziegfield Follies protégée, Eddie Cantor. But Mae West left no film record of the blackface she wore while doing Bert Williams imitations at the beginning of her career in New York. It was gone by the time she went Hollywood.

Should we try to erase blackface? If you did a thorough job, all of these performers would have to go. You would have to go without both Spike Lee, who made a movie about blackface, and D. W. Griffith, who made a movie with blackface. You end up without Jimmy Rogers, Bob Wills and Hank Williams, all of whom began their careers by blacking up. No George C. Wolfe. No Irving Berlin. And that would be just the start. After you finished your purge of history, and gotten rid of your thousands, you would turn around and see all around you, still growing, a popular culture which was formed by cross racial impersonation, and is still being so formed.

Tags: Al Jolsen·Andy Samberg·Ben Stiller·Bert Williams·Bill Robinson·Bob Cole·Bob Wills·Brian De Palma·Camille A. Brown·Charles Correll·Chris Parnell·Cliff Edwards·Cool White·D. W. Griffith·Donna Reed·Duke Ellington·Eddie Cantor·Ethel Shutta·Fred Astaire·Freeman Gosden·Gary Cooper·George C. Wolfe·George M. Cohan·George Raft·George Washington Dixon·Hank WIlliams·Irving Berlin·J. Rosamond Johnson·James Weldon Johnson·Jimmy Rogers·Jimmy Stewart·Judy Garland·Kay Thompson·Mabel Thompson·Mae West·Martin Lawrence·Michael Jackson·Ossie Davis·Robert De Niro·Shirley Temple·Spike Lee·Tim Moore·Tyler Perry·Wallace Stevens·Willie Best

December 5th, 2012 by Anne Richardson · Interviews

.

Will Vinton, David Altschul, William Fiesterman and Marilyn Zornado at a 25th anniversary screening of The Adventures Of Mark Twain at the Whitsell Auditorium.

.

Will Vinton and Bob Gardiner won Oregon’s first Oscar in 1975 for their stop motion tour de force, CLOSED MONDAYS. Will grew up in McMinnville and began making films as an architecture student at Berkeley (where he happened to hear lectures given by Sheldon Renan!). The list of award winning animators trained at Will Vinton Studio includes Craig Bartlett, Barry Bruce, Joan Gratz, Brad Schiff (PARANORMAN), Travis Knight (CORALINE, PARANORMAN) and Mark Gustafson (THE FANTASTIC MR. FOX). Will continues to teach stop motion animation at Northwest Film Center.

.

Anne Richardson: Will, when you arrived here after Berkeley and were starting to make CLOSED MONDAYS, you were able to support yourself with day jobs working as a filmmaker. What was your very first job?

.

Will Vinton: I was initially hired by Dan Biggs, who was working for Northwestern, Inc. doing industrial documentaries. They had a recording studio and a nice little sound stage. This was in the days when Tektronix was big. Companies like that spent alot of money on media. Georgia Pacific was one of Dan’s big clients.

.

Anne Richardson: This is training films? Sales films?

.

Will Vinton: Training, sales, those were the main things. We did corporate image films. Maybe one third of the work was commercials. I was hired to do editing. Maybe about a year into working at Northwestern, Dan wanted to split off and service the Georgia Pacific accounts himself. So we decided to found Odyssey Productions. Bill DeWeese, the industrialist at Esco, had been a client in the past, so they worked out some terms, and he came on board. Reagan Ramsay, myself, Dan Biggs were the worker bees. Bill DeWeese was the president. Dan put together a terrific board of directors: Patty Kaplan, who was head of Evans Products Co.; Tom Moyers, Sr., Moyers Theaters; Bob Farrell, Farrell’s Ice Cream. The idea was to create a base of really good, strong, big clients – Evans, Tektronix, Georgia Pacific, Louisiana Pacific – and to base a company around doing commercials and industrials, but with the intention of growing to do entertainment.

.

Anne Richardson:

Homer Groening set up his own advertising agency in 1958. Were you aware of him?

.

Will Vinton: Oh yeah. In fact I edited one of his productions. During the time I was freelancing for Northwestern, I did one for Homer which (laughs) I’ve always thought of as a cross between e. e. cummings and Benny Hill.

.

Anne Richardson: You told me once about finding help when you had to build special equipment to shoot claymation.

.

Will Vinton: When I was just starting out, I didn’t have a synchronizer, couldn’t afford one. Somebody told me about Walt Dimick whose father was a machinist and kind of a wild mechanical guy. I went to talk to him, and he felt sorry for me, and gave me a bunch of sprockets and hardware necessary to build a synchronizing part which allowed me to hold my film in place.

.

Anne Richardson: Did you have that same kind of mentor relationship with Homer Groening?

.

Will Vinton: No. I was just hired to do a freelance job. But it was important to me because it was one of my first jobs in Portland.

.

Anne Richardson: Did you feel inspired by Homer’s career?

.

Will Vinton: Well, you have to consider the films! Neither the e. e. cummings part or the Benny Hill part seemed to be exactly what I wanted to do. (laughs) What I did like about Homer COMPLETELY was the kind of wild freedom. That anything’s possible, and someone will pay you to do it.

.

Anne Richardson: Thank you, Will.

.

A crash course on Will Vinton’s place in Portland film history can be found here.

Tags: Barry Bruce·Benny Hill·Bill DeWeese·Bob Farrell·Bob Gardiner·Brad Schiff·Craig Bartlett·Dan Biggs·David Altschul·e. e. cummings·Homer Groening·Joan Gratz·Marilyn Zornado·Mark Gustafson·Patty Kaplan·Sheldon Renan·Tom Moyers Sr·Travis Knight·Walt Dimick·Will Vinton·William Fiesterman

December 5th, 2012 by Anne Richardson · Interviews

.

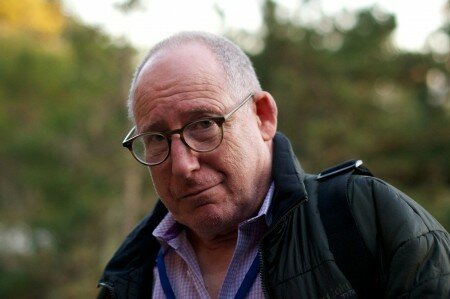

When National Endowment of the Arts put Sheldon Renan on a funding panel in 1970, he wasted no time persuading them to fund a network of four regional film centers. 40 years later, all four – including Northwest Film Center – are still going strong. After a lifetime of reading, writing, producing, directing, watching and just plain loving film, he currently writes and consults about the importance of connectivity. Sheldon Renan grew up in Oregon City and graduated from Cleveland High School in 1957.

.

Anne Richardson: When you went off to Yale, did you have any glimmer of a glimpse that you would become a filmmaker?

.

Sheldon Renan: No. I grew up on a turkey farm. My senior year we moved from Oregon City into Portland and I was three blocks from Reed College. I had a jazz program on the radio station, but the most important thing was every Friday night there were foreign film showings in the chapel.

.

Anne Richardson: You said you wrote An Introduction To The American Underground Film because you had seen all the movies. You were inspired by the lack of a guide, because one didn’t exist?

.

Sheldon Renan: It was a combination of things. I’d seen alot of the movies. Andy Warhol had asked me to write a book about him. It was just a sense that there needed to be a book. I got into the Junior Council at the Museum of Modern Art just when they were doing an exhibition of underground film, their first one. Willard Van Dyke was taking over as director and I think I claimed I was doing a history of and introduction to underground film. It just popped out of my mouth. What often happens is that I tell a lie, and then it sounds like a good idea. So I go ahead and do it.

.

Anne Richardson: And it changed everything.

.

Sheldon Renan: In 1968, I was in New York to meet Henri Langlois, and there was a knock on the door one morning, and a butler was standing there, holding a plate with a top on it. He said “Is Sheldon Renan here?” He lifts the top off the plate, and it was an invitation to have lunch at a mansion across the street. So I go to the lunch and there’s Jean DeMenil (CEO of Schlumberger, an international oil fields equipment company), Henri Langlois, Simone Swan, and, to my amazement, Francois Truffaut and Fritz Lang. I was so upset I popped a button off my suspenders. Literally in front of Truffaut and Lang, I had to have my button sewed back on. So I asked Fritz if he would come out (to Berkeley’s Pacific Film Archives) and do a film series. I was trying to write my first script at the time and Fritz kinda became my coach.

.

Anne Richardson: So your primary identity is as a writer.

.

Sheldon Renan: Yes. Its too complicated to explain that I sometimes produce and sometimes direct. I never know what I am doing until the phone rings.

.

Anne Richardson: When you were at the NEA, your main input was “I don’t think it (federal funding for film) should all go to American Film Institute.”

.

Sheldon Renan: I wanted to create something for everybody because if it wasn’t for everybody I would be excluded. I’m doing what I do about film and filmmaking so that people won’t have a hard time finding their way into the kitchen the way I had.

.

Anne Richardson: Thank you, Sheldon.

.

More about Sheldon Renan:

.

What keeps his interest these days

His place in Portland film history

Tags: Andy Warhol·Francois Truffaut·Henri Langlois·Jean DeMenil·Sheldon Renan·Simone Swan·Willard Van Dyke